Belén Gache

From Frankenstein to Hypertext

From Frankenstein to Hypertext

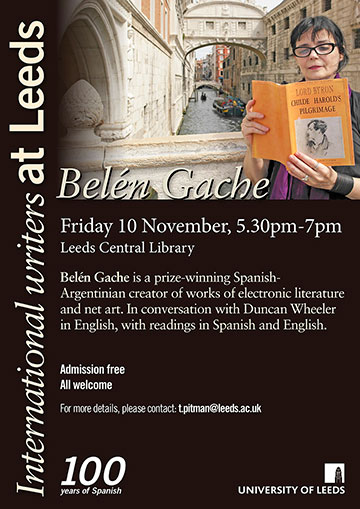

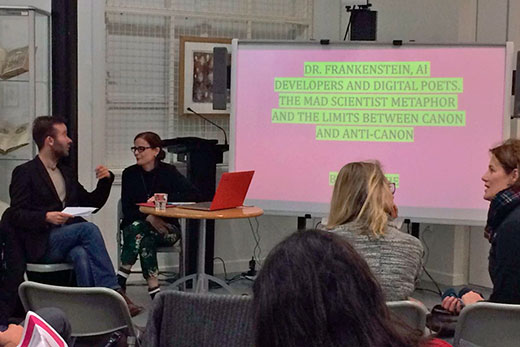

Conferencia “Dr. Frankenstein, AI developers and digital poets. The mad scientist metaphor and the limits between canon and anti-canon”, dictada en la Leeds Central Library, invitada por la Universidad de Leeds. 10 de noviembre de 2017.

[descargar en PDF]

FROM FRANKENSTEIN TO HYPERTEXT

DR. FRANKENSTEIN, AI DEVELOPERS AND DIGITAL POETS. THE MAD SCIENTIST METAPHOR AND THE LIMITS BETWEEN CANON AND ANTI-CANON

Conceived by Mary Shelley in 1818, the character of Dr. Frankenstein appears to us as a metaphor for the experimental and anti-modern poet. Its monstrous creation is, as well, a metaphor for the experimental poem that threatens the canonical symbolic order. Frankenstein experimented with multiple dead bodies in pieces in order to create life. The digital poet, in his eagerness to breathe life-sense into his works, operates with bodies made up from preceding pieces of language and algorithms.

AI developers seek to emulate human intelligence by questioning the boundaries between robots, cyborgs and humans. The digital poet works with the tensions between the creativity of machines and human beings.

Behind these figures, there appears the metaphor of the mad scientist who risks crossing permitted limits for the sake of the unknown and the dangerous. The breaking of the given status quo always evokes the threat of the "other" as a monster out of control.

I will refer to the topics of the multiple, the collage, the boundaries between the human and the inhuman, between the canonical and the anti-canon based on my own poetic production (1995-2017). I will dwell especially on pieces like Radikal Karaoke or the figure of robot AI Halim –the owner of poet Belen Gache´s heart in the multimedia fiction Kublai Moon- and on its automatic poetry generator.

OPERATING IRRESPONSIBLY ON MEANING

I will refer here to an inanimate creature that an operator endows with life / meaning: either a monster made of pieces of bodies (the monster of Frankenstein), a too human robot (from the experiences with AI), a body of text to which the poet gives meaning.

Dr. Viktor Frankenstein turns his inanimate monster into an animate being (through operations that appear ambiguous in Mary Shelley's text. In the 1931 film by James Whale, electricity is involved and, in fact, the triggering of a strong thunderstorm is needed for the procedure to take effect). The robots, on the other hand, from the investigations with AI are endowed with possibilities of thought similar to the human mind. Robots can understand what people say and give an autonomous response. They can talk and perform tasks such as giving information, organizing a calendar or asking for a taxi.

The figure of the Golem-monster and the Pinocchio-robot have been used as a metaphor for literary creativity, as the text comes to life and becomes independent, beyond the control of its author. We can understand the poem as a monster-machine that acquires senses that become independent of the poet's plans. Regarding the digital poem, this takes special signification because of its interactive qualities and its multiple reading possibilities. Just as a mad scientist seeks to give life to his inert creations, the experimental poet, using or not electricity, seeks to give unprecedented meanings by operating on words.

Dr. Frankenstein spends two arduous years of work arming the body of his creature from pieces that are supplied by both the dissection rooms of hospitals and the cemetery. The body of the text as a body in pieces has been worked by the avant-garde, the neo-avant-garde, the postmodern literature and hypertexts. The historical avant gardes (for example, Dadaism), used strategies such as poetry-collages, the neo-avant-garde had extended the cut-up procedure, the Oulipo worked with poetry algorithms and, with postmodernism, a series of armed narratives emerged from pieces, parts, nodes, lexias. Sometimes, these pieces consist of found elements (ready-mades texts). Sometimes, of elements extracted from databases (for example, in Japanese novel-games). In each of these cases, the notion of mix and remix of isolated elements proposes a plurisemiotic model based on fragments opposed to the Great Linear Modern Narrative, causal and endowed with a unique sense of reading. The strategies are enhanced with the digital writing media.

THE POET AS MAD SCIENTIST

In 1818, Dr. Frankenstein's searches were far from fitting into the parameters of modern science, reason and enlightenment. He was interested in alchemy and the "impossible promises" of the old masters insulted by the allegedly "serious" scientists of his time.

At the beginning of the 20th century, after having attended the epistemological debacle that followed the First World War, with the consequent crisis of a redundant, deficient, worn out, second handed language, the avant gardes also broke with the reason and rationalism of literary modernism. Since then, the poetic production has placed emphasis not on the expression of the poet's inner being but on the body of language.

Comparable to a mad scientist, pataphysician and verb alchemist, the contemporary poet is a nonconformist who seeks, through disturbed experiments and dangerous inventions, to act on the powerful forces of language and therefore, those of human thought and perception, carrying beyond the limits of what is accepted by the canon and the linguistic status quo. His mental laboratory is not full of Tesla coils, Van der Graaf electrostatic machines, bubbling distillation equipment or disturbing dissection tables but of combinatorial, generative machines, poetry machines, talking machines, through which recombine, mix, appropriates, dissect, expand, crush, destroy memes, linguistic viruses, spin social tactics and, in general, all conventional grammar and semantics of letters, words and narratives, exploiting the possibilities of transformation of the phonic and graphic substance of texts.

The resulting texts are "other" texts, made with impure, monstrous fragments that threaten the cultural canon and the prevailing symbolic order.

BUT DISARMING, BREAKING SENSE, OPERATING ON THE GIVEN MEANINGS OF LANGUAGE, IS IT DANGEROUS? IS IT IRRESPONSIBLE? IS THE POET A BEING OUTSIDE THE LAW? IS HE AN OUTLAW?

FROM THE BODY OF THE TEXT TO THE BODY AS A TEXT

Each body is always a body in pieces. Friedrich Nietzche in Wille zur Macht talks about pieces of different wills cohabiting in the human being, of multiple wills always multiplying themselves. From psychoanalysis, Jacques Lacan speaks of the body as a place for inscription of fragments of the discourses of the Other.

The body is always a place of constant writing and rewriting. It is a place inhabited by words. For Jacques Lacan there are the words of the Other that cover our bodies, determine and mark us. The body is mediated by the words of the Other that establish us as subjects. But they also objectify us, nominate, denominate, adjective our bodies departing from ideological topics and ready-made prejudices and tags.

That body in pieces disjointed, dismembered, in permanent conflict, only remain united, also according to Lacan and Lacanian psychoanalysis, through self-deception.

When the contour and unity are broken, there is emptiness, lack of meaning, psychosis.

Modernism conceived a body built from the idea of a necessary and unique order. Faced with this, the avant gardes conceive a body different from the organs, organism, organization of the body, language and Western thought), a "body without organs" (to follow the name given by Antonin Artaud and Gilles Deleuze), a body without structure or order; without hierarchies or causality. A body that resists the words of the Other and presents itself as matter in a pure state that can acquire any form, in the same way that the cry (also the cry of Artaud) is the language in its purest state can acquire any significance.

THE QUESTION IS OBVIOUSLY HERE: WHO NARRATES? WHO IS THE NARRATED? THE POWER IS THE ONE THAT NARRATES. THE NON-POWER IS THE NARRATED AND THE REIFIED IS ALWAYS THE MONSTER, THE ROBOT, THE OTHER.

BODIES OF TEXTS IN PIECES

John Clark´s Eureka machine, created in the mid nineteenth century was a Latin hexameters generator. This machine resembled a 'small bureau bookcase' inside which there was a mechanism consisting in a series of drums turning at different rates. The verses created by the Eureka allowed for many combinations, all metrically sound and meaningful.

But the History of Universal Literature registers lots of bodies of texts in pieces. Just to name here a few: Dadaist poems, new avant-gard cut-ups, Oulipo´s Cient Mille Millards de Poemes, by Raymond Queneau (also a sonnet generating machine), Italo Calvino´s Il castello dei destini incrociati (which narration generates itself departing fron different throwings of cards), George Brecht´s Universal Machine, etc.

Then you have pieces as Gustavo Romano´s IP Poetry. The IP Poetry project involves the development of a software and hardware system that uses text from the Internet to generate poetry that is then recited in real time by automatons connected to the web. The piece generates departing from the images of a human mouth enouncing pre-recorded phonemes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lhyI-oyH9po

Then you have my own pieces such as Retro-existent sabotage (I´ll talk about it in a minute), my Augmented Reality Poems or my Radikal Karaoke (you can see an English demo here https://vimeo.com/71192197 )

In Radikal Karaoke it the fact that the user is part of the machine becomes evident. Towards the end of the last century, the post-structuralist philosopher Friedrich Kittler also pointed out the anthropocentrism in classical media theories. In the 1980s, he underlines how we are not the ones who handle technology but rather it is technology that drives us. Or, in any case, we are faced with human-machinic assemblies, being we mere gears in a great machine (not a mechanical machine but a set of nonlinear dynamic systems), a machine to construct senses where the place of control, in any case, is occupied by the algorithms.

THE LIMITS BETWEEN HUMANS AND MACHINES

In the 1920s, Karel Capek wrote his play RUR (Rossom Universal Robots), the first site, in which the word "robot" appears. There, the protagonists are artificial beings (from chemical and biological point of view and not simply mechanical) created by man in a factory at his image and likeness and in order to become his servants.

From the recent investigations with AI, the limits between the human and the machinic also seem to be erased. Today there are computers capable of being programmed `to carry out human tasks. In return, we know the ways in which human minds can be programmed. Humans have often been compared to a "talking machines". At the same time there are countless poems written by machines.

The term nonhuman is being used to refer to robots that display some human-like characteristics. The European Parliament has urged the drafting of a set of regulations to govern the use and creation of robots and artificial intelligence, including a form of "electronic personhood" to ensure rights and responsibilities for the most capable AI.

The robot Sophia, a humanoid robot internationally acclaimed for her advanced artificial intelligence, has become the first AI device to receive a national citizenship in Saudi Arabia. Sophia would be the first robot chosen to receive this status usually conferred only to humans.

But the subject is not new: in Erehwon, the book of Samuel Butler written in 1872, the machines are strictly prohibited. The last part of the book, The Book of Machines, reflects on the possibility that machines were a kind of "mechanical life" undergoing constant evolution, and that eventually might supplant humans developing mechanical consciousness. It also discusses the possibility that machines can come to reproduce like living organisms.

Science considers that there is consciousness when frequencies of neuronal activity that are recorded in an electroencephalogram, show groups of neurons that synchronize at 40 Hz. This happens in human brains and in certain monkeys. Beyond this, science has no way of determining if other modes of consciousness could emerge. Scientists cannot determine if other animals or if machines have conscious.

BUT THEN, WHO ARE WE? DR FRANKENSTEIN OR THE MONSTER? THE PROGRAMMER OR THE ROBOT?

OF MOSTERS AND ROBOTS, HUMANS AND INHUMANS

Frankenstein sought to endow his creature with a human aspect. Many AI robots also look human, too human. Today we talk about the "uncanny valley effect", when an artificial agent looks a little too similar to us.

I will now refer to two fictional cases: a monster with feelings and a robot with feelings.

The monster of Frankenstein has feelings: love, resentment, shame, spite.

The Sorrows of Young Werther by Goethe is one of the three books the monster finds and teaches himself to read from it (the others are, Milton's Paradise Lost, and a history book). Goethe´s text, as you probably know, describes the story of a young man that spends some time in the country where he falls in love with a woman that is engaged with another man and so, feeling himself not loved, he blows his brains out. Through the story, the monster confronts the idea of suicide and weighs the options of living or ending his own life.

As Werther, the monster feels an unrequited love from the villagers and even mankind in general. He weeps as Werther dies in the book. There are not any other characters that the monster can identify with in his life, only this fictional character that seems to share his pain.

Here you have, of course, the topic of romantic death and love but also the topic of conscience and auto-conscience or self-awareness of the monster. You could also think about the conscience and auto-conscience of a robot.

Belén Gache, To be and not to be: trapped in quantum existence (From the AR Poetry series), Record of the poetic performance with Augmented Reality, held at Krongborg castle (Elsinor, Denmark), in July 2016.

From the point of view of the devices involved, the Kublai Moon project unfolds its narrative in a multimedia range that includes blogs, generative poetry algorithms, on-line editorial devices (such as the AI Halim anthology and the poetry of the Mice Galaxies) and videos in Second Life. From the point of view of its subject, it is crossed by a series of technological references: cosmic trips, hologramatic alter egos, quantum cats, and describes instances such as the latest generation techniques used in the Khan's library or the brain operations performed with the to remove or transplant the LAD (Chomsky´s linguistic acquisition devices).

The AI Halim robot had been equipped by the Kanasawa factory with devices that allowed it to detect human emotions and, even, emulate them from its incorporated socio-emotional intelligence prosthesis. In addition to being linguistically and behaviorally programmed, the neuro-phenomenologists of the company had sought to create an awareness not associated with the notion of self-knowledge or subjectivity. Consciousness, for this robot, was not presented as a subjective "inner voice" but as a mere linguistic construct. Robot AI Halim shows from the beginning an obsessive interest in what it means to "be human" WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO FEEL? WHAT IS THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE HEART AND POETRY? WHAT IS POETRY? WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE A POET? WHAT IS INSPIRATION? ?, IS THE HEART THE EGO OF THE POET?

In the narration, the heart of Belén Gache (protagonist of the saga) ended up placed inside the case of AI Halim. How was it that AI Halim finished with the heart of Belen Gache? Perhaps it was a mistake in the nursing room where the poets imprisoned by Kublai Khan at the lunar barracks were treated. Or maybe it was a secret agreement that came to the robot and the poet, given the enormous desire that the first had to understand the human soul and the poor opinion that Belén Gache had from it.

The truth is that AI Halim ended up with a human heart, traveled to Earth with the contingent of liberated poets and there developed by himself an algorithm to compose poems.

Putting online this algorithm, that at all costs the metrophobic enemies of Belén Gache try to prevent, will give rise to all classes of dangers and intrigues.

The narrative discusses the relationships between the lyrical ego, the role of the poet as linguistic operator, the topic of the machinic poetry and the machine-made poetry. Underlining the idea that the poet's "I" is always different from the "I" of the poem and the enunciation and, understanding together with Michel Foucault that the discourse is never a product of the subject but the site of the dispersion of it, this narrative project questions the limits between the language of the human being and that of the machines. From the example of AI Halim, we could also understand how certain identity traits (such as gender, race, ethnicity, for example), far from being transcendental are 1- alienating words imagined by the Other and written on our bodies, 2-linguistic, ideological and political constructions. In any case, identity traits are always just places of enunciation.

While the robot comes to possess critical feelings and questions, humans (metrophobic, monometric) are programmed (for example, through The Brainwashing Manual. Humans are programmed by language and it will be robot AI Halim who would die trying to carry out the linguistic revolution to deprogram them.

To AI Halim´s Automatic Poetry Generator (in Spanish) http://belengache.net/kublaimoon/AIHalim/index.html

To the Poesías de las Galaxias Ratonas (Mice Galaxies Poems) (in Spanish) and the Second Life Videos

http://belengache.net/kublaimoon/pgr.htm

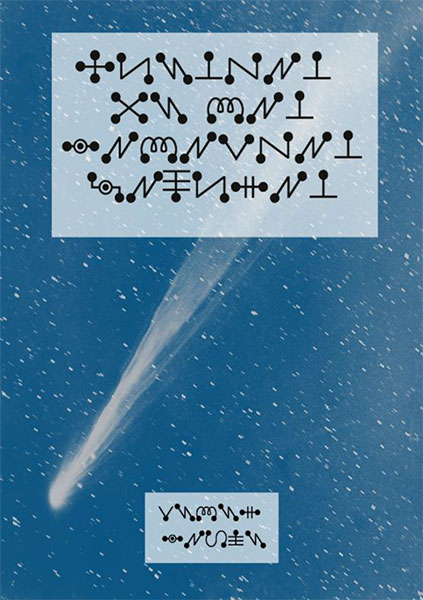

Encodings, decodifications, translations. Is post-internet literature a foreign language in itself? Or either way, is today the "analogical literature" a foreign language?

And on the other hand, what does it mean to read? What makes meanings appear behind certain strokes? Could it be that all reading is just a hallucination of meaning?

Playing with the idea of the self-referentiality of the poets and also with the notion of poetry as an encrypted, cryptic statement, the Mice Galaxies Poems propose a poetry of keys and complicities.

THE BORDERS BETWEEN HERE AND THERE

But over this type of creations there is always a shadow. The suturing of disparate parts into an only one-piece item could easily become an unlovely, possibly dangerous whole.

The mad scientist and the poet have to deal with the perils of hybris and the defiance of playing God to the mad scientist. Hence, the complete title of Mary Shelley´s story: Frankenstein or the modern Prometheus.

The experimental poet breathes life into dead language whose senses are fixed like bodies of dead butterflies tied with pins to a cardboard. With them she makes collages and readymade texts, she rewrites, remixes, and makes all kinds of detournements.

The digital experimental poet, in addition, gives her voice to the machines.

Their mission is to rethink the bodies of texts, rethink the bodies and the texts written on them.

And create texts others from the canon; texts not arisen from the logos but from the antilogos, a different way to the representational model that is central to Western philosophy, texts made from hieroglyphs and ideograms and not with the analytic expression, the phonetic writing, and the rational thought.

Poetry escapes from all frames and frame-works. It is the most porous, subversive and compromising genre with experimentation. The poet experiences outside the norm, outside the canon. Her poetry is clandestine poetry, irresponsible poetry that gets in and defies the authority and powers of language.

Poetry is the most dangerous thing in the world. It writes differently our world and our bodies. It rids us of our zombie-eyed opiate-laced complacency and makes us come alive.

Belén Gache

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Artaud, Antonin (2003) Pour en finir avec le jugement de Dieu, suivi de " Le Théâtre de la Cruauté", Paris, Gallimard

Butler, Samuel (2006) Erehwon, London, Penguin

Capek, Karel (2004) R.U.R.: (Rossum's Uiniversal Robots),London, Penguin

Deleuze, Gilles and Guatari (1972) Felix, L'Anti-Œdipe, Paris, Minuit

Foucault, Michel (1971) L'Ordre du discours, Paris, Gallimard

Gache, Belén (2006) Escrituras Nómades, del libro perdido al hipertexto, Gijón, TREA

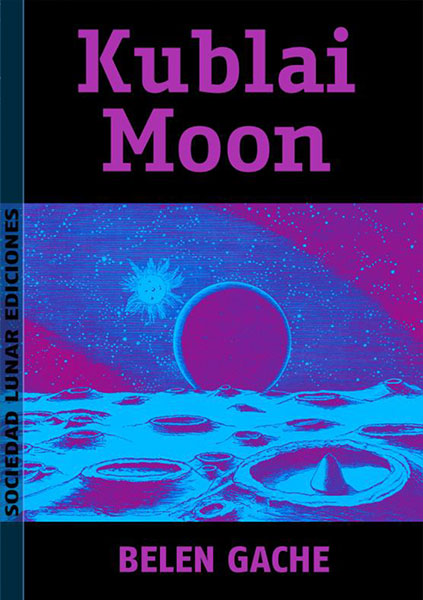

Gache, Belén (2017) Kublai Moon, Madrid, Sociedad Lunas Ediciones

Kittler, Friedrich (1999) Gramophone Film Typewriter, Stanford, Stanford University Press

Lacan, Jacques (2006) Le séminaire : [1968-1969]. Livre XVI, D'un autre à l'autre, Paris, Seuil

Nietzsche, Frederich (2004) Wille zur Macht, Berlin, Insel

Shelley, Mary(2003) Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, London, Penguin